Automated Ball-Strike: A New Pathway for Player Value

How players can derive new value from knowing the strike zone

Players and managers have long resorted to arguing with umpires over ball and strike calls. The new Automated Ball-Strike (ABS) challenge system aims to replace these age-old confrontations with a quick, technology-backed review process that keeps the game moving and gets more calls correct. For over 150 years – ever since umpires began calling balls and strikes in 1864 – players have been battling over the strike zone, leading to “untold number of verbal (and, yes, sometimes even physical) tussles” and frequent ejections. Now Major League Baseball is experimenting with a solution that preserves the human element of umpiring while using the convenience of modern tech: an ABS challenge system being tested in spring training and the minors as a possible fixture in MLB games by 2026. This article will explain how the ABS system works, how it promises to improve the game, and the strategic wrinkle of limited challenges – a new frontier where “challenge success” becomes a skill – and the implications for batters, catchers, and pitchers alike.

How the ABS Challenge System Works

MLB’s ABS challenge system is a compromise between using “robot umpires” for every call and maintaining the traditional home-plate umpire, with a sprinkle of strategy added in. In an ABS-enabled game, the home-plate umpire continues to call balls and strikes as usual – but a Hawkeye-powered tracking system runs in the background, ready to verify any close call. If a player believes the umpire got a call wrong, they can immediately challenge it, and the computer will render a verdict in seconds. Importantly, this is not a free-for-all challenge on every pitch; each team has a limited number of challenges per game, making their use a strategic decision in itself.

ABS Challenge Basics: Major League Baseball tested the following rules during Spring Training 2025:

Limited challenges: Each team is allotted two ball-strike challenges to start the game (with no extra allowances in extra innings). If a challenge is successful (overturning the umpire’s call), the team retains it, but if the call stands, they lose that challenge. In other words, you can keep challenging as long as you’re correct, but once you’ve had two wrong challenges, you’re out for the rest of the game. This mirrors the logic of MLB’s replay review for plays in the field, where a manager keeps their challenge if it’s successful.

Who and how to challenge: Only the players directly involved – the batter, the pitcher, or the catcher – can initiate a challenge, and they must do it immediately after the call. There’s no signaling from the dugout or waiting for a replay; the player simply taps the top of their hat/helmet right away to appeal the call.

Rapid automated review: Once challenged, the ABS system (using multiple cameras and the same Statcast tracking technology in use since 2019) checks the exact pitch location as it crossed the plate. A computer-animated strike zone graphic is then displayed on the stadium video board (and TV broadcast) showing where the pitch was and whether it was in or out of the zone. The whole process is incredibly quick – adding roughly 15 seconds per challenge on average. In spring trials, each challenge took about 13.8 seconds on average, down from ~16–17 seconds in the AAA tests. With only about 4 challenges total per game being exercised on average, that’s less than a minute of added game time – a virtually unnoticeable impact on pace.

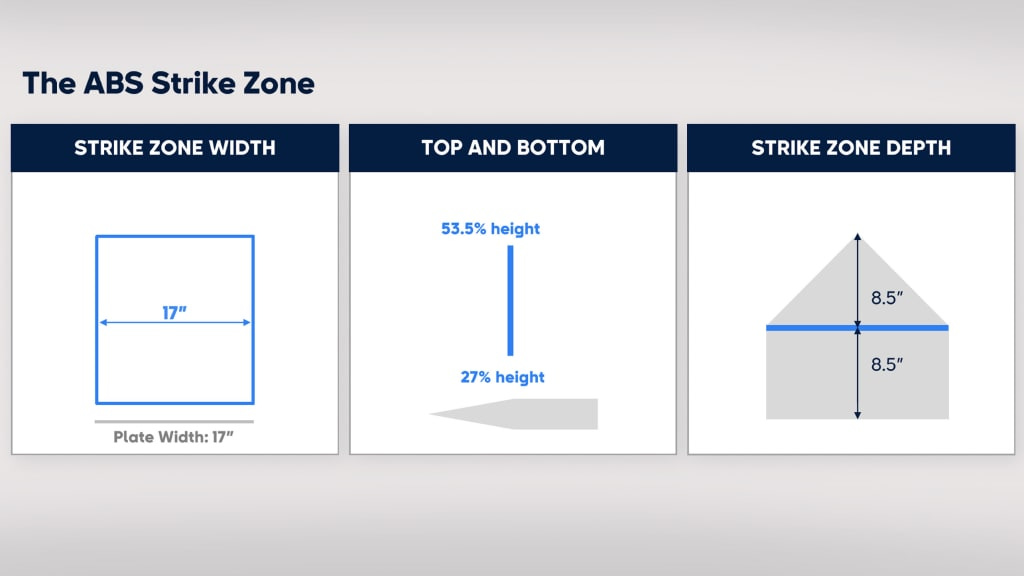

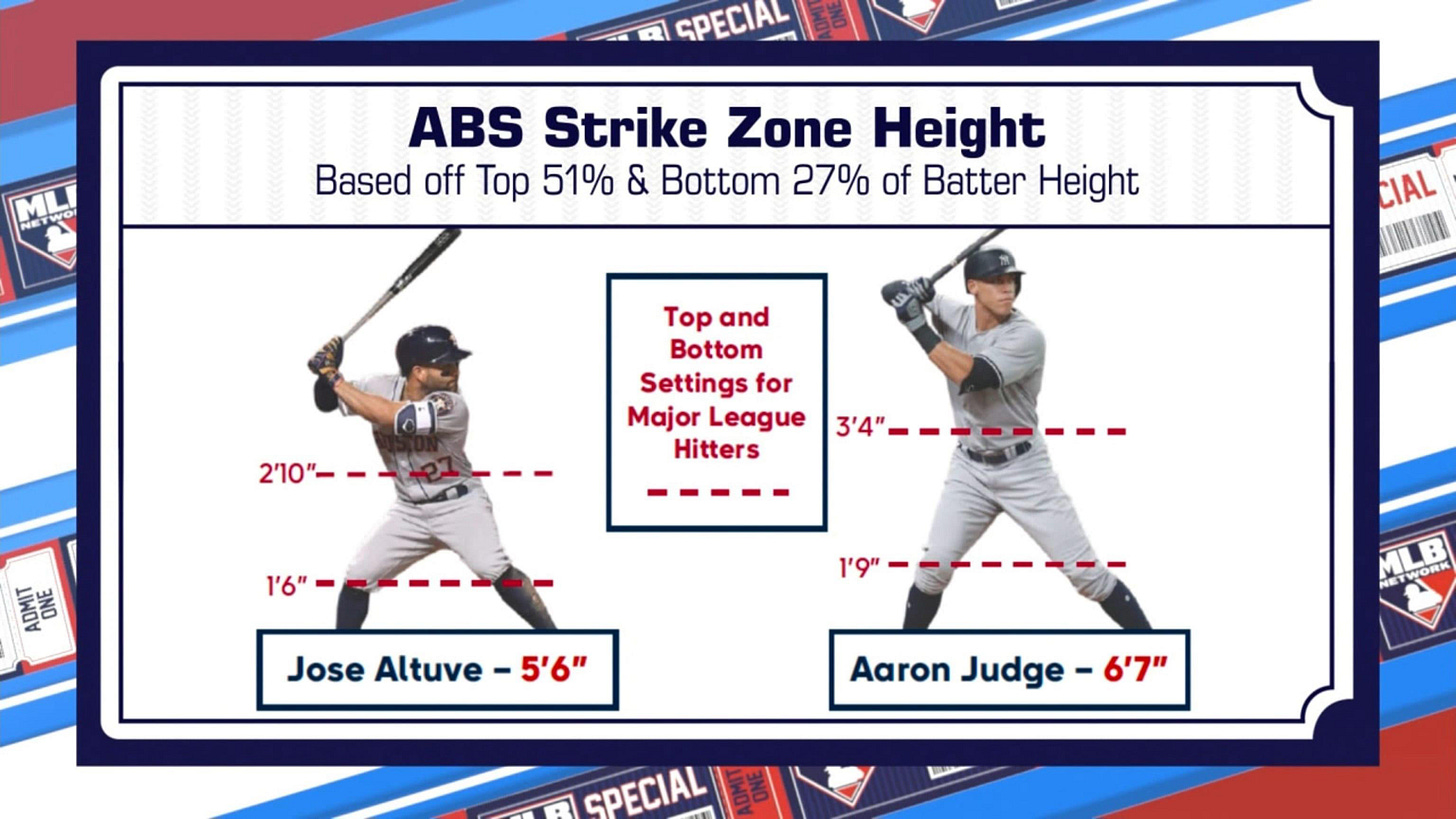

Calibrated strike zone: The ABS strike zone is adjusted for each batter’s height (measured in advance by MLB), so that the top and bottom of the zone are set at specific percentages of the player’s height. This ensures the automated zone truly matches the rule-book strike zone for tall or short players. (Umpires’ zones can vary; studies found the human-called zone tends to be a bit more forgiving on the upper and lower edges than the precise ABS zone)

Strategy on a New Frontier: Limited Challenges and the Art of Challenge Success

One of the most intriguing aspects of the ABS system is the layer of strategy it adds to a part of the game that previously had none. Under pure human umpiring, a player has no strategic recourse on balls and strikes – you either accept the call or argue (and risk ejection). Under a full robot-ump system, there’d be accuracy but zero discretion or strategy. The challenge system, however, introduces a resource to be managed: a limited number of appeals that can be used at the players’ discretion. This means teams must decide when a situation is important enough to risk a challenge, and players must develop a feel for which calls they’re likely to get overturned. In essence, ball-strike challenges have made judiciousness and judgment into explicit on-field skills. The concept of “challenge success” – how often you win the challenges you attempt – could emerge as a measurable skillset that could differentiate players and teams.

Data from the spring training trial demonstrates this point. With challenges capped at two (unless you keep winning them), players tended to save them for key moments – but success varied. Roughly 44% of challenges on high-leverage two-strike counts (2-2 or 3-2) were successful, compared to 57% on first-pitch challenges. That suggests that players were more willing to gamble on a borderline call in a do-or-die count, whereas they only challenged a first pitch if they were quite certain the umpire blew the call. In other words, early in a plate appearance or game, players exercised restraint, conserving their challenge unless it was an obvious miss; later, especially with two strikes, they were more apt to say “why not?” and hope for a reversal. The overall overturn rate did decline as the game went on – 60% success in the first three innings, down to ~45% in the late innings – likely as players became more desperate or used their remaining challenges on iffier calls. This dynamic shows that choosing when to challenge can be just as critical as the act of challenging itself. Savvy teams might soon treat challenges like timeouts in basketball or football – a strategic asset to deploy at just the right juncture.

Because only pitchers, catchers, and batters can initiate challenges, those individuals need to sharpen their real-time judgment. There is no checking with a replay room or coach (unlike MLB replay reviews on base-running plays); the call to challenge is instantaneous and comes from the field. This has led to interesting early trends: catchers, in particular, seem to excel at making wise challenges. In ABS test games, catchers had a 56% success rate on challenges they initiated, much higher than the 41% success rate for pitchers who challenged. (Batters were near the overall average at ~50%.) Catchers often have the best view of the pitch and an inherent understanding of the strike zone, so it makes sense that they’ve been effective at knowing when an umpire got one wrong. Going forward, teams might empower catchers to make the call on whether to appeal a ball/strike, much as they quarterback the pitch-calling and field positioning. We may even see challenge guru catchers become valuable – those with a reputation for getting calls overturned reliably could save runs by turning would-be walks into strikes (or vice versa).

All of this points to “challenge success” becoming a tracked metric. It’s not hard to imagine front offices and analysts calculating each player’s challenge success percentage, or how many runs a team saved (or gained) via successful challenges over a season. A player who consistently wins, say, 70% of his challenges could be providing a real competitive edge, effectively stealing strikes back from the umpire. On the flip side, a player who burns through challenges frivolously might earn a reputation and cost his team opportunities later. Judgment under pressure becomes part of the game – a psychological and tactical battle layered onto the physical confrontation of pitcher vs. hitter.

Batters: Zone Experts Get Their Due

Hitters with elite strike-zone awareness have long been admired by front offices and fans, and under ABS their discipline will become even more of a weapon. A batter who knows the zone better than the umpire does can effectively nullify umpire error to his disadvantage. If a pitch is outside the zone but called a strike, a confident hitter can challenge and get the call corrected to a ball – essentially turning an umpire’s mistake into an opportunity (extending his at-bat or even earning a walk). This means hitters who traditionally suffered from tight umpire zones will get a fair shake, and those who already seldom chase bad pitches will be even tougher outs.

Consider Juan Soto, often cited as “one of the greatest artists of the strike zone we’ve ever seen”. Soto’s plate discipline is almost mythical – in 2021 he was the only qualified MLB hitter with more walks than strikeouts, and he routinely posts a walk rate above 20%. With Soto’s keen eye, if an umpire rings him up on a pitch an inch off the corner, you can bet Soto will know it. Under the challenge system, he can immediately appeal that call, and given his skill, it’s likely the ABS will vindicate him. In fact, during spring trials, Soto wasted no time showcasing this: in one game he instantly challenged a called strike that he knew was outside – sure enough, the ABS replay showed it missed the zone, the call was overturned, and Soto went on to draw a walk in that plate appearance. In the past, that missed call might have simply been strike three and an frustrated Soto; now his elite eye actively earns tangible benefits for his team.

Max Muncy is another great example – a power hitter with patience who sports a 15.8% walk rate since 2018 (5th-best among qualified hitters). Muncy has a reputation for laying off pitches just off the plate. With ABS challenges, Muncy can ensure those borderline takes truly go his way. Before the Dodgers took the field for their first spring game with the ABS system, Dave Roberts had one rule for Max Muncy: “Save your challenges.” Muncy is famously selective at the plate and known for arguing borderline calls. Naturally, he ignored his manager’s advice, challenged a strike call anyway, and got it overturned. Even when he’s on the other side of a challenge, Muncy “couldn’t blame” the pitcher for challenging because he knew the ball was a strike. In the long run, disciplined hitters like Muncy will likely challenge very selectively and successfully, avoiding wasted appeals. The net result: these zone hawks will reach base even more and be even harder to pitch to unfairly.

Catchers: From Framing Artists to Challenge Generals

No position in the field is more affected by a strike zone change than the catcher. For the past decade, pitch framing (the subtle art of receiving pitches to “steal” strikes on the edges) has become a prized skill. Catchers who excel at framing have literally earned their teams extra strikes and outs, and teams have paid and traded for catchers with great framing metrics. What happens to that value when an automated system can effectively override bad calls or even call the zone perfectly? The full robo-ump scenario would have largely erased framing from the game – a big reason many players were hesitant about it. The ABS challenge system, however, preserves the human umpire’s calls as the default, meaning framing still matters initially, but with an important caveat: truly egregious misses can be corrected after the fact. This nuanced change means catchers will likely shift their focus toward situational awareness and game management over pure framing prowess.

In the ABS challenge format, a well-framed pitch that fools an umpire but was actually a ball won’t do much good if the batter challenges and overturns it. Conversely, a poorly framed pitch that leads an umpire to call a ball on what was actually a strike can still be fixed by a challenge from the defense. Thus, the value of stealing strikes by framing is diminished, because the incorrect calls it tries to create or avoid are less likely to stand. We saw in spring training data that catchers were often the ones initiating challenges on behalf of their pitchers, and they did so with a high success rate. It appears that catchers are already transitioning from solely trying to influence the umpire to also leveraging the ABS system when needed. In essence, the catcher’s role evolves into a dual responsibility: receive the pitch as well as possible to get the right call from the umpire, but instantly recognize and correct any mistake via challenge. The best catchers will be those who can balance these two tasks – present pitches well and know when that doesn’t work and a challenge is warranted.

We may soon talk about a catcher’s challenge management the way we talked about framing. A catcher with a sharp eye and quick decision-making might save a team’s challenges for key spots and signal the pitcher to challenge only when he’s sure. On the flip side, a catcher who impulsively taps his helmet on every close call could burn through the team’s allotment too early. This is where situational awareness becomes paramount. Expect catchers to consider the game context: inning, score, count, who is batting, who is pitching, and the importance of that base runner or out. For instance, a catcher might decide not to challenge a borderline ball four in the 3rd inning with a lesser hitter at the plate, preferring to save the challenge for a possible game-changing moment later. However, in the 9th inning of a one-run game, that same catcher will pounce on a miss if it could turn a walk into an out. This kind of tactical thinking aligns with the traditional role of the catcher as the field general. The difference is now they have a new tool in their arsenal.

Another impact on catchers is in roster valuation. Some glove-first catchers who built their value largely on framing might see a dip in usefulness if that skill is less game-changing. Meanwhile, catchers who are strong in other areas – throwing, game-calling, hitting – could see a relative rise in value, since framing won’t set them apart as much. That said, framing won’t vanish overnight with the challenge system (umps still call most pitches and not every borderline will be challenged), so teams will still want catchers who can present pitches well. But if and when ABS challenges arrive in MLB, front offices might start to downweight framing in their defensive metrics. They’ll instead watch metrics like a catcher’s challenge success rate and how often his pitchers benefit from overturned calls. It’s quite likely teams are already studying which catchers worked in the ABS system in Triple-A and how it affected pitching performance (and if they aren’t, they should give me a job).

Indeed, by the end of 2024 testing, players had signaled they didn’t want framing to become irrelevant – one reason MLB gravitated to the challenge system rather than full automation. The challenge system is that middle ground: it preserves much of the catcher’s traditional role but trims the extremes of umpire error. Going forward, we’ll likely see catchers embrace technology (perhaps subtly getting feedback from the bench or bullpen cameras on whether a pitch was in the zone, although officially no outside help is allowed) and truly become masters of the strike zone on both sides of the plate, helping their team by any means – either a quiet frame or a quick challenge tap.

Pitchers: Changing the Mental Game

For pitchers, the ABS challenge system is both a safety net and a new strategic frontier. Pitchers live on the black edges of the plate – stealing a strike at the knees or just nicking the outside corner can be the difference between a strikeout and a walk. Under the human ump system, painting the corner is an art that sometimes goes unrewarded if the umpire doesn’t give the call. Under full ABS, every true strike would be a strike (good for pitchers with great control), but the human element of working an umpire or expanding the zone would disappear. With the challenge system, pitchers get a bit of the best of both worlds. They can still attempt to get calls just off the plate (and hope an ump gives it to them), but if they throw a pitch that should be a strike and it’s incorrectly called a ball, they have recourse.

A clear early example was Cody Poteet’s first challenge of Spring Training. Poteet, a fringe roster pitcher, delivered a perfect low strike that was initially called a ball. Thanks to ABS, he confidently challenged, got the strike, and subsequently struck out the batter (Max Muncy) because the count flipped in his favor. After the game, Poteet remarked that “every strike matters” – a simple quote that speaks volumes. Pitchers put immense effort into hitting their spots in sequence; knowing they can claim those strikes even if the umpire misses one gives them added confidence to execute their game plan. We might see pitchers nibble the corners even more aggressively when they have a challenge in their pocket. For instance, a pitcher might deliberately aim a fastball at the very edge of the zone on a 3-2 count – if the ump calls it a ball, the pitcher can immediately challenge, hoping to turn what would’ve been ball four into strike three (or at least into a full count instead of a walk). This means pitchers with excellent control and knowledge of the zone could benefit greatly. A veteran with pinpoint command or a cerebral pitcher who studies the zone (think of a Greg Maddux type or today someone like Kyle Hendricks) could effectively bank strikes via challenges.

There is also a mind-game element. Pitchers and catchers might subtly let hitters know they’re willing to challenge. Imagine a pitcher glaring in after a borderline call and tapping his cap – a signal that, “I’ll challenge if you take that pitch again.” It could potentially shrink a batter’s effective hitting zone, knowing the pitcher will fight for every strike. On the other hand, pitchers must be careful not to overuse challenges on marginal calls driven by emotion. The data showing pitchers’ low success rate (only 41% of pitcher-initiated challenges were upheld in spring) suggests some pitchers might impulsively challenge pitches they hope were strikes but actually weren’t. The best pitchers will likely lean on their catchers or their own discipline to only challenge when they’re reasonably sure. Just as a wild pitcher can get into trouble walking batters, a pitcher who “wildly” challenges everything will find himself out of challenges quickly.

Finally, consider the impact on pitcher psychology. Part of a pitcher’s job is handling adversity – like a bad call – without unraveling. The challenge system provides a constructive outlet for that frustration. Instead of stewing over a missed strike three, the pitcher can channel that emotion into a quick challenge and get back to work. This could mean fewer emotional meltdowns on the mound and possibly even fewer manager ejections on behalf of their pitchers. It’s a bit like giving pitchers a “reset” button for bad calls. In aggregate, that could improve the quality of pitching we see, as hurlers feel the system has their back on truly bad misses. This was one of my biggest flaws as a pitcher and I absolutely wish I had this when playing. A few consecutive calls not going your way can throw you out of rhythm, completely derail an inning, and sometimes the outcome of the game.

A Better Game Through Innovation

Baseball is a game of unbelievably small margins, and nowhere is that more apparent than in the definition of a strike. The Automated Ball-Strike challenge system ensures those margins are called correctly, and it does so in a way that enhances the game’s integrity without sacrificing its soul. By allowing a limited number of challenges, MLB has found a sweet spot that keeps the drama and strategy alive. There is still an art to pitching, batting, and catching – in fact, that art is now joined by a bit of game theory in deciding when to challenge. We will likely see a new kind of baseball IQ celebrated: the catcher who knows the perfect moment to challenge, the batter who never wastes an appeal, the pitcher who confidently uses a challenge to get that extra strike he earned. Challenge success could become as much a talking point as arm value or framing runs.

For front offices, the ABS system will prompt adjustments in how players are valued and coached, but it offers more reward than risk. Ensuring the correct calls on the most pivotal plays means outcomes (and player stats) will be more reflective of true performance rather than umpire error. Over a 162-game season, that could be the difference of a few wins – and in a pennant race, that is huge. Informed fans will appreciate the nuance: yes, the challenge system brings a bit of the chess match mentality to balls and strikes, but it doesn’t bog down the sport. If anything, it provides immediate talking points (“Should he have challenged there? Did you see Soto challenge that strike and end up walking?”) and adds transparency.

As we look ahead, the ABS challenge system appears poised to do what replay review eventually did – become a natural, even beloved, part of the game. We can envision a future where a big ABS challenge in the 9th inning is just as replayable on highlight shows as a walk-off hit. And when we see catchers tapping their helmets or pitchers smirking as the graphic on the board shows they painted the corner, we’ll know the game has taken a step forward. It’s baseball, just a little smarter. By blending human tradition with technological precision, MLB is striving for a product that is both more fair and more fun. The early returns suggest that the ABS system, with its unobtrusive nature and strategic flavor, is on track to improve the game in exactly those ways – a win for front offices, players, and fans alike.